In brief seconds

What does “home” mean? Is it the roof and four walls? Or is it the mementos and Polaroid photos you use to adorn it? For certain individuals, a house may represent many things, but one thing always exists there: safety. However, home is a concept that is difficult to define for thousands of migrants throughout the globe.

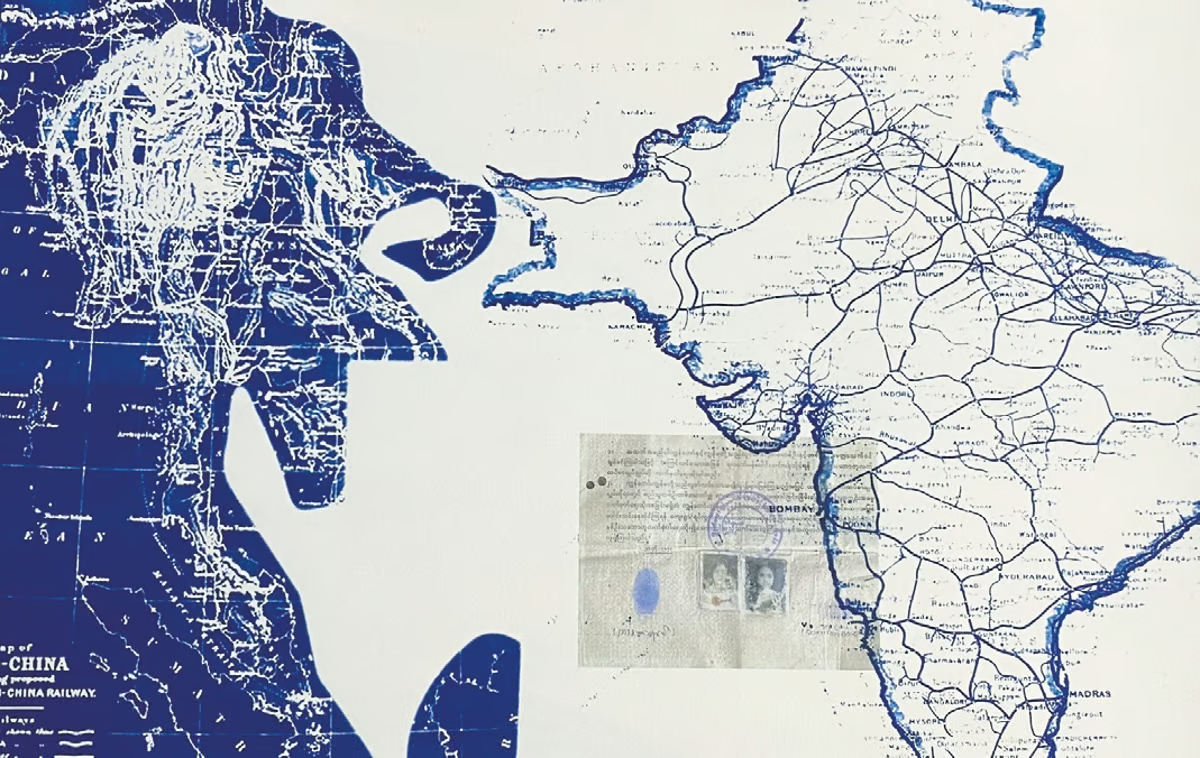

Dilpreet Bhullar, a writer and researcher, will be presenting A Home in the Constant Flux: A Call to the Verb Memory, a picture series exhibition that explores the lived experiences of refugees, to help us understand their transience. Through a distinctive visual story, the exhibition, organized by museologist Manan Shah, conveys the fleeting aspect of migrants’ lives.

According to Bhullar, “the seed for the series was planted when I was researching Rohingya refugees.” She discovered a hole in the narrative and visual portrayal of their experiences while doing her investigation. She was motivated by this disparity to produce a body of work that both chronicles and elevates the experiences of refugees.

Bhullar, who is hesitant to identify as an artist, says, “When I was working on this piece about the Rohingya refugees, I found myself imagining what I would like to see as an artist if I was on the other side of the spectrum – the intentions and the visual language that would resonate with me.” The 36-photo series was produced as a result of this contemplation.

Through conversations with refugees who are now residing in Jammu Kashmir and New Delhi, the idea took on a new shape. I owe a great deal of gratitude to the families who let me into their homes and hearts so that I could tell their tale. I was able to continue working on the project for over 2.5 years since most of these exchanges were unexpected and chance-based, according to Bhullar.

The use of cyanotype, a photographic printing technique that creates pictures in Prussian blue, is fundamental to Bhullar’s art. This method, which has traditionally been used to geological records and building plans, is utilized as a metaphor for the unstable and sometimes unpredictable lives of migrants. Through the technique of overlaying digitized photos of personal items gathered from these refugee households with archive maps, Bhullar effectively conveys the relationship between materiality and memory. “Because citizens become refugees for a variety of reasons, their identity as the political selves slips into in-betweenness, so both maps and objects defy the inherent notion of permanency,” the author claims.

The exhibition’s most notable aspect is its emphasis on things, which spotlights individual possessions as opposed to the typical portraiture connected to refugee documentation. “The surge of visuals overpowered me in 2017,” says Bhullar, “when the infamous massacre of the community in Myanmar flooded the news and simultaneously in Europe we were watching incoming refugees from Syria, Africa on rickety boats, crossing the barbed wires.” She also recalls an essay published as a visual response to the 1947 Partition by American woman photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White. And I realized that photojournalists working now have not changed the visual vocabulary of recording migrants since that time.

Bhullar changes the focus of the story from one of survival to one of identity and memory. These artifacts, infused with political and personal history, provide the refugees with concrete connections to their pasts. The photojournalists’ use of long views, top shots, and noise-affected faces of the migrants seemed to be an infringement on their privacy. Nobody was interested in learning the fate of the migrants. According to Bhullar, “the objects enable them to share intimate stories that inextricably link into the larger political history of their displacement.”