In the AMU Minority Status Debate, Fundamental Rights Take precedence over laws passed by parliament: CJI

The Supreme Court of India recently addressed the long-running dispute over Aligarh Muslim University’s (AMU) minority status, representing a major legal advance. Before the Supreme Court, the Central government had said that AMU could not be categorized as a university associated with a particular faith or denomination. Any organization that the government considered to be of national significance was not allowed to claim minority status.

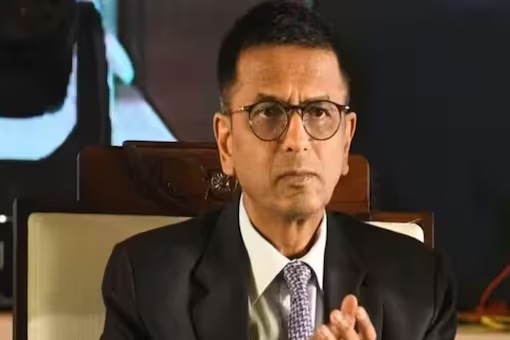

For many years, AMU’s minority status has been embroiled in a legal dispute. The Supreme Court reaffirmed the fundamental rights of religious and linguistic minority communities under Article 30 of the Constitution in response to this. The bench, which included Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud and Justices Sanjiv Khanna, Surya Kant, JB Pardiwala, Dipankar Datta, Manoj Misra, and Satish Sharma, was composed of these judges. According to the Times of India, the court emphasized that the establishment and management of educational institutions could not be subject to restrictions regarding degrees, faculty and facilities, or government support.

Attorney General R Venkataramani said that Article 30 was an enabling article, highlighting the fact that the establishment of an educational institution of a certain kind required the legal competence or authority granted. Chief Justice Chandrachud raised a noteworthy point when he observed that the right guaranteed by Article 30 seemed to be contingent on the provisions of a bill passed by Parliament. The CJI emphasized, “Mere establishment of an institution by legislature-enacted law would not take away its’minority’ character.”

The court continued by declaring that no group, including minorities, could establish an institution in the modern era if the University Grants Commission (UGC) Act or other relevant laws were not followed. The court recognized the hard realities of financing, pointing out that receiving subsidies had no bearing whatsoever on an institution’s denominational identity and that very few institutions could exist without government assistance.

Venkataramani said that he didn’t want to suggest that legislation approved by Parliament trumped Article 30 rights in response to the court’s findings. He emphasized that the ability to create a certain class of institutions must be traced back to an enabling act in order to guarantee that the choice component under Article 30 remains unconstrained within the legal framework. This legal discussion is an important part of the intricate story of AMU’s minority status.