Kashi: An evening with the current

India views Varanasi, or Kashi, as an old place hanging in an uninterrupted continuity rather than as a building site. Its existence is rooted far deeper than Ayodhya in the cultural imagination, interwoven with centuries-old personal socio-religious histories—cycles of birth and death. This air is also inhaled by the residents. When you keep hearing the phrase, “Paanch hazaar saal purana sheher,” real antiquity is a historical diversion. Thus, Kashi’s unusual luck lies in navigating between those “five thousand years” and the five-year cycles of contemporary democracy.

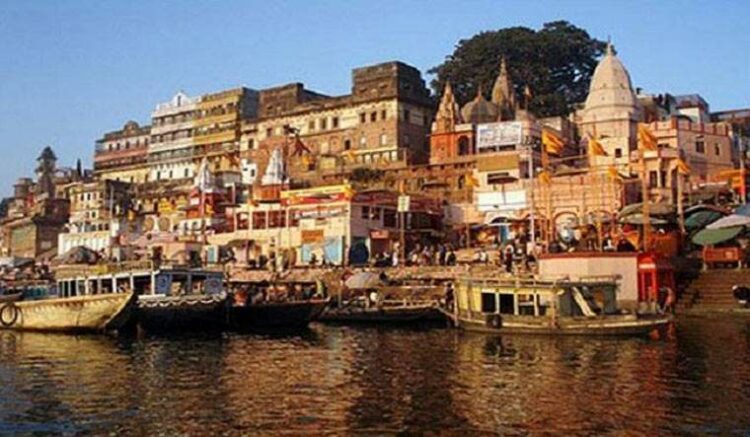

Elections for the 18th Lok Sabha are scheduled for 2024. Naturally, here too there is a certain form of continuity at work—a prime leader seeking a third term in office. From the ghats, as it were, which loom like sentinels above a lived experience, an air of confidence rises. Raised up into the heart of the city, you are thrust into a busy desi lifescape in all its modern diversity. Here, you’ll discover a constant flow of chatter punctuated by a number of animated streetcorners.

Apart from antiquity, other current eras seem to cohabit here. Within the Baba Vishwanath temple, there is a large, brand-new, 21st-century hallway. Its tall walls, adorned with rectangular-patterned stone work, uncannily evoke Soviet architectural design. With its century-old Indo-Gothic elegance, the Banaras Hindu University oozes appeal. Of course, the 17th-century architecture of the Gyanvapi mosque often makes front-page news. Like a trapeze artist, Varanasi navigates its position beneath the hot sun, stuck between Hindutva and skyscrapers, juggling its old-world purpose with its newfound VIP-ism.

It’s a nervous living situation. The traditional spiritual ambiance is gradually disappearing as a result of the current tourist surge. similar to much of ancient India. About 300 new guesthouses have sprung up in only a 15-minute walk up from Dashaswamedh Ghat to accommodate the influx of religious travelers from Pune, Rajkot, Meerut, Coimbatore, and even Seoul. Many of these tourists are young. In the evening, people take seats on plastic chairs and watch a Ganga aarti through bamboo arches illuminated by bulbs. This new spirituality is not silent; contemporary music systems resound with mantras, bhajans, and finally the Maha Tandav Aarti.

Kashi’s agreement between the traditional and contemporary

It feels as if even the refreshing river breeze is holding its breath till it passes.

The hoi polloi rubs shoulders with BHU academics, the occasional poet, or locally made intelligentsia at the Pappu ki Adi tea shop, where even PM Modi once came by for a drink of its legendary lemon tea. The current political climate is unavoidable, even if the city seems to be rather detached from the commotion on TV. It’s weirdly refreshing. Varanasi votes only on June 1st in the seventh round, so maybe we catch the fever at its earliest stages. However, there’s no indication of a wave or story to make that lemon tea explode. Politics seems to be carved out of a high, rectangular stone pattern that repeats itself: Modi hi aayega.

There isn’t much room for speculation—the main question, if any, is regarding win margins. What percentage of votes Modi will get? This time, will it be 10 lakh? In the western part of the state, turnout has been modest. Varanasi has to make an impression at the party. During a recent visit, Amit Shah solely engaged in “worker connect,” or orange alert. The elements do, however, make assumptions about the margin. Will state Congress president Ajai Rai, a local tough guy, a seasoned participant in many a Lok Sabha joust, forfeit his deposit or make a genuine challenge? Few think Modi’s popularity might be declining. The delivery of broad-spectrum development, including highways, bridges, bypasses, and yes, the magnificent temple corridor (which looks better in the nighttime), has never been better.

A peculiar voice, befitting a youthful IT specialist, bemoans: “Yeah, but at what expense? It is said that you can now go to the airport in twenty minutes. Why must one reach so quickly? 3,000 trees have been lost as a result of such pace. A population inhaling hazardous air is the result of such depletion. Willn’t it end up costing more in the end? It is not seriously opposed to bringing up these important issues.

Still, the majority of Varanasi is happy with the growth. “My foreign business is still down, not recovered from Covid,” remarks Samir Mathur, whose tourism bureau handles both local and international travel. “The visa regime is still quite restrictive.” However, observe the domestic flow! Apne desh ke taraf dekho (think local) was correct, Modiji. This place has a thriving economy. He is not very patient with other hot-button issues, such as the proposed amendment to the Constitution. “Did Nehru not create the first amendment?” he asks in response. R N Singh, a retired bank official, nods in accord, saying, “Modi has really advanced this area. Better facilities are currently being developed. According to former industrialist and cultural enthusiast Ashok Kapoor, it is India’s unofficial spiritual capital. Here, religion has been effectively harnessed to drive a boom in hospitality.

Not much has changed at the well-known Pahalwan lassi business, which is basically just a glorified kiosk. It is best to savor the lassi and rabri in clay kulhars without looking down at the sodden mess below. This strip of little restaurants is busy, despite the squealing traffic and the constant worry of being driven over by cars and rickshaws. This is neither Kampong Glam or Little India in the vein of Singapore, where the Oriental is retained in all its splendor among practical contemporary aesthetics. Not yet, anyhow. Like the rest of desi India, Varanasi still screams for attention from the public due to its extreme chaos. All that’s left of old Kashi is an exhilarating buzz that stretches from the ghats to the city. The contrast is accentuated by the trip to the tranquil cantonment, where everything is kept in proper order, even the roads and the trees.

A few grumbles drift carefully across the atmosphere like hesitant murmurs. Too many tourists. Things are becoming too costly. There is still an unequal distribution of compensation for people who had to move to make room for the corridor. Nevertheless, “Modi is not challenged.” Varanasi’s demographics—6.5 lakh SAVarna, 6 lakh OBC, and 1 lakh Dalit—make it a safe seat for the BJP. The last two are not beyond being seduced by Hindutva. The odds are too great, even if Rai manages to get all 3 lakh Muslim votes along with a healthy dose of his own Bhumihar Brahmins, notwithstanding predictions of core vote subsidence.

It makes sense that Priyanka Gandhi never bothered to reply to Mamata Banerjee’s proposal to run for office from this position. It was much more difficult for Rai since, up until the night before his name was revealed, there were rumors that he was attempting to defect to the BJP. Ratnakar Tripathi, a former spokesperson of the NSUI, is humble in his ambition: “Modi will win, but ‘400 paar’ is a distant dream.” The topics of discussion include unemployment, price increases, Agniveer, electoral bonds, and a non-consultative method of operation. Thoda mohbhang hua hai signifies a hint of disillusionment. Nothing is said here about the BJP or Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, either positively or negatively. Only Modi is involved. Even though Yogi reportedly makes weekly trips to Varanasi to keep an eye on things.

Amidst the growth, the Banarasi saree—a disappearing art form—is surrounded by a profound grief. “Our traditional weavers are receiving less assistance as powerlooms have become more prevalent. Few people in our nation still possess the ability to weave the fabled saree, according to Abhishek Sharma, a policeman tasked with escorting VIPs and visitors around the temple. With his skill in weaving through the maze of narrow streets, he can recount every detail of Varanasi, even the subtleties of Aurangzeb’s actions.

In a city that is like a stream of consciousness—a city characterized by a river unlike any other—unspoken words likewise pass silently by you. In a city where the sound of Bismillah Khan’s shehnai will never reverberate in the crisp morning air, Liaquat Ali continues to sell flowers that devotees may gift to Baba Vishwanath in exchange for blessings.